2024 Rewind: Orthogonal Polynomial Regression in Bambi

A deep dive into what orthogonal polynomials actually do under the hood, contributed to Bambi’s examples

Back in 2024, I wrote a couple of example notebooks that got merged into the Bambi documentation. For those unfamiliar, Bambi is a library for fitting Bayesian regression models using a formulaic interface on top of PyMC (the closest thing in python to brms, in my opinion). I realized I never migrated the content here, so I thought it was time to do so.

This post covers polynomial regression. The original notebook lives in the Bambi docs.

What follows is the content from the notebook, lightly adapted for this blog format.

Unlike many other examples shown in Bambi, there aren’t specific polynomial methods or families implemented – most of the interesting behavior for polynomial regression occurs within the formula definition. Regardless, there are some nuances that are useful to be aware of.

This example uses the kinematic equations from classical mechanics as a backdrop. Specifically, an object in motion experiencing constant acceleration can be described by the following:

\[x_f = \frac{1}{2} a t^2 + v_0 t + x_0\]where \(x_0\) and \(x_f\) are the initial and final locations, \(v_0\) is the initial velocity, and \(a\) is acceleration.

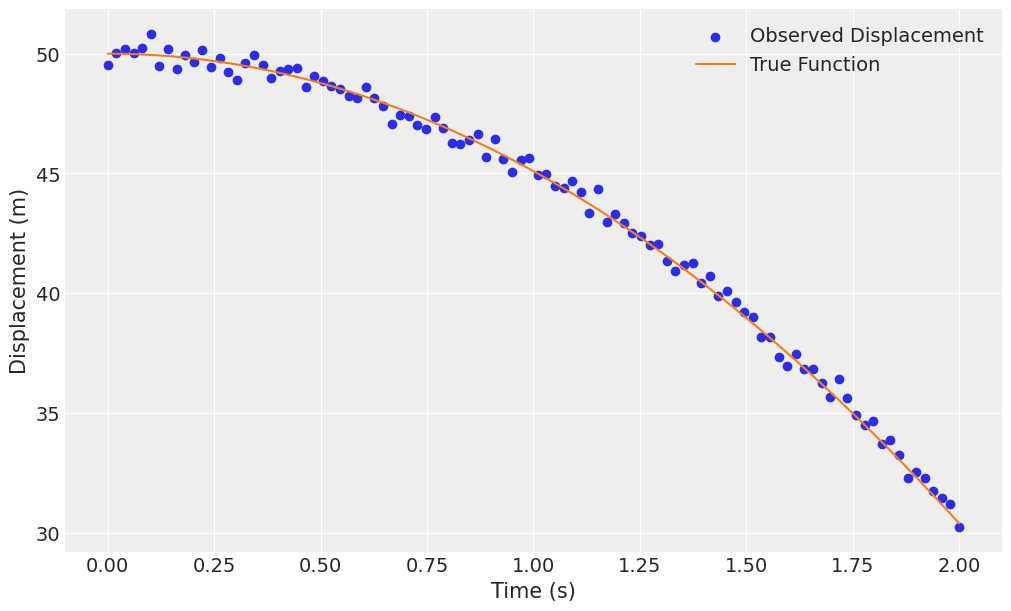

First, we’ll consider a simple falling ball, released from 50 meters. In this situation, \(v_0 = 0\) \(m\)/\(s\), \(x_0 = 50\) \(m\) and \(a = g\), the acceleration due to gravity, \(-9.81\) \(m\)/\(s^2\). So dropping out the \(v_0 t\) component, the equation takes the form:

\[x_f = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 + x_0\]We’ll start by simulating data for the first 2 seconds of motion. We will also assume some measurement error with a gaussian distribution of \(\sigma = 0.3\).

import warnings

import arviz as az

import bambi as bmb

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

SEED = 1234

az.style.use("arviz-darkgrid")

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

g = -9.81 # acceleration due to gravity (m/s^2)

t = np.linspace(0, 2, 100) # time in seconds

inital_height = 50

x_falling = 0.5 * g * t**2 + inital_height

rng = np.random.default_rng(SEED)

noise = rng.normal(0, 0.3, x_falling.shape)

x_obs_falling = x_falling + noise

df_falling = pd.DataFrame({"t": t, "x": x_obs_falling})

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.scatter(t, x_obs_falling, label="Observed Displacement", color="C0")

ax.plot(t, x_falling, label="True Function", color="C1")

ax.set(xlabel="Time (s)", ylabel="Displacement (m)")

ax.legend();

Casting the equation \(x_f = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 + x_0\) into a regression context, fitting:

\[x_f = \beta_0 + \beta_1 t^2\]We let time (\(t\)) be the independent variable, and final location (\(x_f\)) be the response/dependent variable. This allows our coefficients to be proportional to \(g\) and \(x_0\). The intercept, \(\beta_0\) corresponds exactly to \(x_0\), the initial height. Letting \(\beta_1 = \frac{1}{2} g\) gives \(g = 2\beta_1\) when \(x_1 = t^2\), meaning we’re doing polynomial regression. We can put this into Bambi via the following, optionally including the + 1 to emphasize that we choose to include the coefficient.

model_falling = bmb.Model("x ~ I(t**2) + 1", df_falling)

results_falling = model_falling.fit(idata_kwargs={"log_likelihood": True}, random_seed=SEED)

The term I(t**2) indicates to evaluate inside the I. For including just the \(t^2\) term, you can express it in any of the following ways:

I(t**2){t**2}To verify, we’ll fit the other two versions as well.

model_falling_variation1 = bmb.Model(

"x ~ {t**2} + 1", # Using {t**2} syntax

df_falling

)

results_variation1 = model_falling_variation1.fit(random_seed=SEED)

model_falling_variation2 = bmb.Model(

"x ~ tsquared + 1", # Using data with the t variable squared

df_falling.assign(tsquared=t**2)

)

results_variation2 = model_falling_variation2.fit(random_seed=SEED)

print("I{t**2} coefficient: ", round(results_falling.posterior["I(t ** 2)"].values.mean(), 4))

print("{t**2} coefficient: ", round(results_variation1.posterior["I(t ** 2)"].values.mean(), 4))

print("tsquared coefficient: ", round(results_variation2.posterior["tsquared"].values.mean(), 4))

I{t**2} coefficient: -4.8476

{t**2} coefficient: -4.8476

tsquared coefficient: -4.8476

Each of these provides identical results, giving -4.9, which is \(g/2\). This makes the acceleration exactly the \(-9.81\) \(m\)/\(s^2\) acceleration that generated the data. Looking at our model summary,

az.summary(results_falling)

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97% mcse_mean mcse_sd ess_bulk ess_tail r_hat

sigma 0.336 0.025 0.289 0.381 0.000 0.000 5977.0 2861.0 1.0

Intercept 49.961 0.051 49.870 50.058 0.001 0.001 5997.0 3145.0 1.0

I(t ** 2) -4.848 0.028 -4.899 -4.799 0.000 0.000 5704.0 2844.0 1.0

We see that both \(g/2 = -4.9\) (so \(g=-9.81\)) and the original height of \(x_0 = 50\) \(m\) are recovered, along with the injected noise.

We can then use the model to answer some questions, for example, when would the ball land? This would correspond to \(x_f = 0\).

\[0 = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 - x_0\] \[t = \sqrt{2x_0 / g}\]calculated_x0 = results_falling.posterior["Intercept"].values.mean()

calculated_g = -2 * results_falling.posterior["I(t ** 2)"].values.mean()

calculated_land = np.sqrt(2 * calculated_x0 / calculated_g)

print(f"The ball will land at {round(calculated_land, 2)} seconds")

The ball will land at 3.21 seconds

Or if we want to account for our measurement error and use the full posterior,

calculated_x0_posterior = results_falling.posterior["Intercept"].values

calculated_g_posterior = -2 * results_falling.posterior["I(t ** 2)"].values

calculated_land_posterior = np.sqrt(2 * calculated_x0_posterior / calculated_g_posterior)

lower_est = round(np.quantile(calculated_land_posterior, 0.025), 2)

upper_est = round(np.quantile(calculated_land_posterior, 0.975), 2)

print(f"The ball landing will be measured between {lower_est} and {upper_est} seconds")

The ball landing will be measured between 3.2 and 3.23 seconds

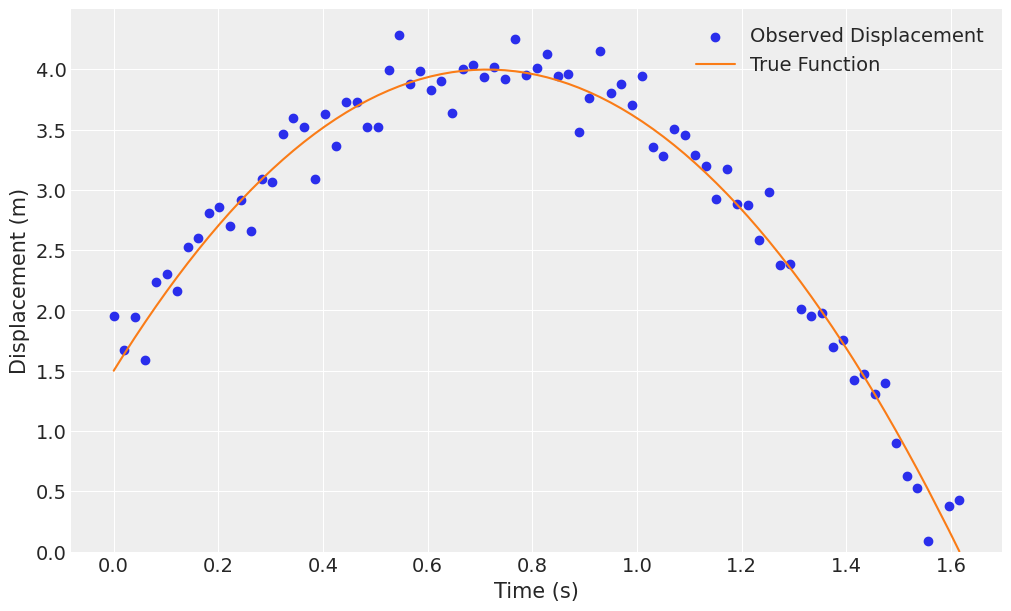

Next, instead of a ball strictly falling, instead imagine one thrown straight upward. In this case, we add the initial velocity back into the equation.

\[x_f = \frac{1}{2} g t^2 + v_0 t + x_0\]We will envision the ball tossed upward, starting at 1.5 meters above ground level. It will be tossed at 7 m/s upward. It will also stop when hitting the ground.

v0 = 7

x0 = 1.5

x_projectile = (1/2) * g * t**2 + v0 * t + x0

noise = rng.normal(0, 0.2, x_projectile.shape)

x_obs_projectile = x_projectile + noise

df_projectile = pd.DataFrame({"t": t, "tsq": t**2, "x": x_obs_projectile, "x_true": x_projectile})

df_projectile = df_projectile[df_projectile["x"] >= 0]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.scatter(df_projectile.t, df_projectile.x, label="Observed Displacement", color="C0")

ax.plot(df_projectile.t, df_projectile.x_true, label='True Function', color="C1")

ax.set(xlabel="Time (s)", ylabel="Displacement (m)", ylim=(0, None))

ax.legend();

Modeling this using Bambi, we must include the linear term on time to capture the initial velocity. We’ll do the following regression,

\[x_f = \beta_0 + \beta_1 t + \beta_2 t^2\]which then maps the solved coefficients to the following: \(\beta_0 = x_0\), \(\beta_1 = v_0\), and \(\beta_2 = \frac{g}{2}\).

model_projectile_all_terms = bmb.Model("x ~ I(t**2) + t + 1", df_projectile)

fit_projectile_all_terms = model_projectile_all_terms.fit(

idata_kwargs={"log_likelihood": True}, target_accept=0.9, random_seed=SEED

)

az.summary(fit_projectile_all_terms)

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97% mcse_mean mcse_sd ess_bulk ess_tail r_hat

sigma 0.202 0.017 0.171 0.234 0.000 0.000 2723.0 2328.0 1.0

Intercept 1.561 0.066 1.441 1.687 0.001 0.001 2058.0 2550.0 1.0

I(t ** 2) -4.867 0.114 -5.079 -4.649 0.003 0.002 1667.0 1966.0 1.0

t 6.909 0.189 6.553 7.262 0.005 0.003 1694.0 2039.0 1.0

hdi = az.hdi(fit_projectile_all_terms.posterior, hdi_prob=0.95)

print(f"Initial height: {hdi['Intercept'].sel(hdi='lower'):.2f} to "

f"{hdi['Intercept'].sel(hdi='higher'):.2f} meters (True: {x0} m)")

print(f"Initial velocity: {hdi['t'].sel(hdi='lower'):.2f} to "

f"{hdi['t'].sel(hdi='higher'):.2f} meters per second (True: {v0} m/s)")

print(f"Acceleration: {2*hdi['I(t ** 2)'].sel(hdi='lower'):.2f} to "

f"{2*hdi['I(t ** 2)'].sel(hdi='higher'):.2f} meters per second squared (True: {g} m/s^2)")

Initial height: 1.43 to 1.69 meters (True: 1.5 m)

Initial velocity: 6.54 to 7.28 meters per second (True: 7 m/s)

Acceleration: -10.16 to -9.27 meters per second squared (True: -9.81 m/s^2)

We once again are able to recover all our input parameters.

In addition to directly calculating all terms, to include all polynomial terms up to a given degree you can use the poly keyword. We don’t do that in this notebook for two reasons. First, by default it orthogonalizes the terms making it ill-suited to this example since the coefficients have physical meaning and we want to directly interpret them. The orthogonalization process can be disabled by the raw argument of poly, but we still elect not to use poly here because in later examples we decide to use different effects on the \(t\) term vs the \(t^2\) term, and doing so is not easy when using poly. However, just to show that the results match when using the raw = True argument, we’ll fit the same model as above.

model_poly_raw = bmb.Model("x ~ poly(t, 2, raw=True)", df_projectile)

fit_poly_raw = model_poly_raw.fit(idata_kwargs={"log_likelihood": True}, random_seed=SEED)

az.summary(fit_poly_raw)

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97% mcse_mean mcse_sd ess_bulk ess_tail r_hat

sigma 0.201 0.017 0.172 0.234 0.000 0.000 3066.0 2205.0 1.0

Intercept 1.561 0.067 1.437 1.682 0.001 0.001 2535.0 2154.0 1.0

poly(t, 2, raw=True)[0] 6.911 0.196 6.556 7.280 0.004 0.004 2092.0 2075.0 1.0

poly(t, 2, raw=True)[1] -4.870 0.118 -5.095 -4.653 0.003 0.002 2059.0 2166.0 1.0

We see the same results, where poly(t, 2, raw=True)[0] corresponds to the coefficient on \(t\) (\(v_0\) in our example), and poly(t, 2, raw=True)[1] is the coefficient on \(t^2\) (\(\frac{g}{2}\)).

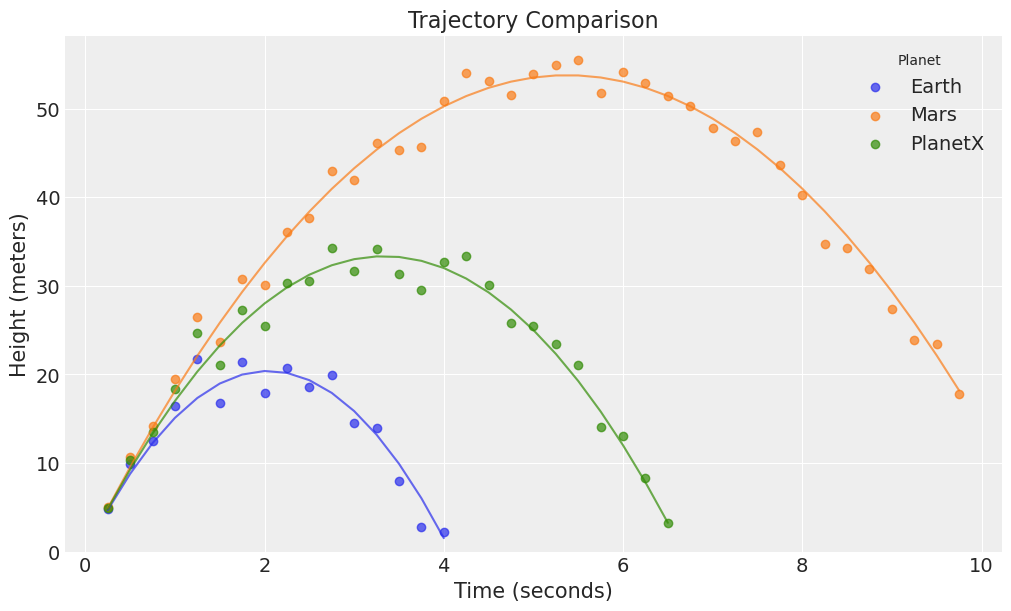

In the next example, you’ve been recruited to join the space program as a research scientist, looking to directly measure the gravity on a new planet, PlanetX. You don’t know anything about this planet or its safety, so you have time for one, and only one, throw of a ball. However, you’ve perfected your throwing mechanics, and can achieve the same initial velocity wherever you are. To baseline, you make a toss on planet Earth, warm up your spacecraft and stop at Mars to make a toss, then travel far away, and make a toss on PlanetX.

First we simulate data for this experiment.

def simulate_throw(v0, g, noise_std, time_step=0.25, max_time=10, seed=1234):

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

times = np.arange(0, max_time, time_step)

heights = v0 * times - 0.5 * g * times**2

heights_with_noise = heights + rng.normal(0, noise_std, len(times))

valid_indices = heights_with_noise >= 0

return times[valid_indices], heights_with_noise[valid_indices], heights[valid_indices]

# Define the parameters

v0 = 20 # Initial velocity (m/s)

g_planets = {"Earth": 9.81, "Mars": 3.72, "PlanetX": 6.0}

noise_std = 1.5

# Generate data

records = []

for planet, g in g_planets.items():

times, heights, heights_true = simulate_throw(v0, g, noise_std)

for time, height, height_true in zip(times, heights, heights_true):

records.append([planet, time, height, height_true])

df = pd.DataFrame(records, columns=["Planet", "Time", "Height", "Height_true"])

df["Planet"] = df["Planet"].astype("category")

And drawing those trajectories,

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

for i, planet in enumerate(df["Planet"].cat.categories):

subset = df[df["Planet"] == planet]

ax.plot(subset["Time"], subset["Height_true"], alpha=0.7, color=f"C{i}")

ax.scatter(subset["Time"], subset["Height"], alpha=0.7, label=planet, color=f"C{i}")

ax.set(

xlabel="Time (seconds)", ylabel="Height (meters)",

title="Trajectory Comparison", ylim=(0, None)

)

ax.legend(title="Planet");

We now aim to model this data. We again use the following equation (calling displacement \(h\) for height):

\[h = \frac{1}{2} g_{p} t^2 + v_{0} t\]where \(g_p\) now has a subscript to indicate the planet that we’re throwing from.

In Bambi, we’ll do the following:

Height ~ I(Time**2):Planet + Time + 0

which corresponds one-to-one with the above formula. The intercept is eliminated since we start from \(x=0\).

planet_model = bmb.Model("Height ~ I(Time**2):Planet + Time + 0", df)

planet_model.build()

planet_fit = planet_model.fit(chains=4, idata_kwargs={"log_likelihood": True}, random_seed=SEED)

The model has fit. Let’s look at how we did recovering the simulated parameters.

az.summary(planet_fit)

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97% mcse_mean mcse_sd ess_bulk ess_tail r_hat

sigma 1.759 0.147 1.498 2.044 0.003 0.003 2054.0 1938.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Earth] -4.998 0.075 -5.145 -4.865 0.002 0.001 1833.0 2431.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Mars] -1.884 0.022 -1.925 -1.844 0.001 0.000 1428.0 1763.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[PlanetX] -3.017 0.036 -3.087 -2.953 0.001 0.001 1519.0 1729.0 1.0

Time 20.128 0.166 19.827 20.449 0.004 0.003 1393.0 1714.0 1.0

Getting the gravities back to the physical value,

hdi = az.hdi(planet_fit.posterior, hdi_prob=0.95)

print(f"g for Earth: {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'Earth', 'hdi':'lower'}):.2f} "

f"to {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'Earth', 'hdi':'higher'}):.2f} "

f"meters (True: -9.81 m)")

print(f"g for Mars: {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'Mars', 'hdi':'lower'}):.2f} "

f"to {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'Mars', 'hdi':'higher'}):.2f} "

f"meters (True: -3.72 m)")

print(f"g for PlanetX: {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'PlanetX', 'hdi':'lower'}):.2f} "

f"to {2*hdi['I(Time ** 2):Planet'].sel({'I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim':'PlanetX', 'hdi':'higher'}):.2f} "

f"meters (True: -6.0 m)")

print(f"Initial velocity: {hdi['Time'].sel(hdi='lower'):.2f} to {hdi['Time'].sel(hdi='higher'):.2f} "

f"meters per second (True: 20 m/s)")

g for Earth: -10.29 to -9.71 meters (True: -9.81 m)

g for Mars: -3.85 to -3.68 meters (True: -3.72 m)

g for PlanetX: -6.18 to -5.90 meters (True: -6.0 m)

Initial velocity: 19.80 to 20.45 meters per second (True: 20 m/s)

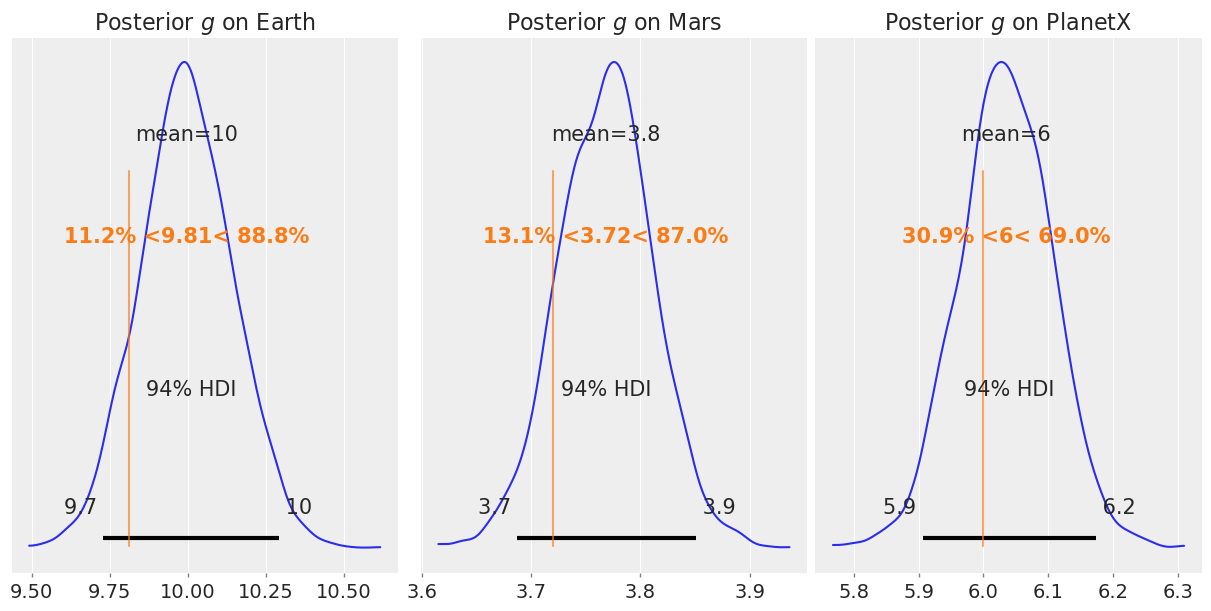

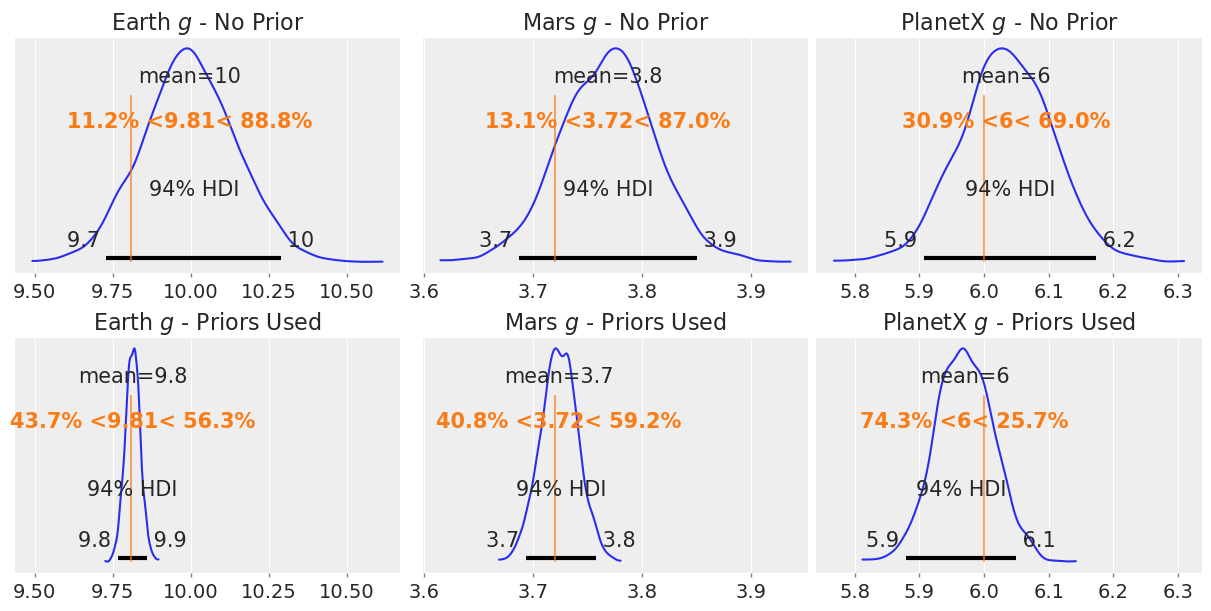

We can see that we’re pretty close to recovering most the parameters, but the fit isn’t great. Plotting the posteriors for \(g\) against the true values,

earth_posterior = -2 * planet_fit.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "Earth"})

planetx_posterior = -2 * planet_fit.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "PlanetX"})

mars_posterior = -2 * planet_fit.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "Mars"})

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 6))

az.plot_posterior(earth_posterior, ref_val=9.81, ax=axs[0])

axs[0].set_title("Posterior $g$ on Earth")

az.plot_posterior(mars_posterior, ref_val=3.72, ax=axs[1])

axs[1].set_title("Posterior $g$ on Mars")

az.plot_posterior(planetx_posterior, ref_val=6.0, ax=axs[2])

axs[2].set_title("Posterior $g$ on PlanetX");

The fit seems to work, more or less, but certainly could be improved.

But, we can do better! We have a very good idea of the acceleration due to gravity on Earth and Mars, so why not use that information? From an experimental standpoint, we can consider these throws from a calibration mindset, allowing us to get some information on the resolution of our detector, and our throwing apparatus. With informative priors constraining the Earth and Mars gravity parameters, the model can more precisely estimate the unknown PlanetX gravity, as there will be less uncertainty propagating from the calibration planets.

For Earth, at the extremes, \(g\) takes values as low as 9.78 \(m\)/\(s^2\) (at the Equator) up to 9.83 (at the Poles). So we can add a very strong prior,

\[g_{\text{Earth}} \sim \text{Normal}(-9.81, 0.025)\]For Mars, we know the mean value is about 3.72 \(m\)/\(s^2\). There’s less information on local variation readily available by a cursory search, however we know that the radius of Mars is about half that of Earth, so \(\sigma = \frac{0.025}{2} = 0.0125\) might make sense, but to be conservative we’ll round that up to \(\sigma = 0.02\).

\[g_{\text{Mars}} \sim \text{Normal}(-3.72, 0.02)\]For PlanetX, we must use a very loose prior. We might say that we know the ball took longer to fall than Earth, but not as long as on Mars, so we can split the difference. Then set a very wide \(\sigma\) value.

\[g_{\text{PlanetX}} \sim \text{Normal}(\frac{-9.81 - 3.72}{2}, 3) = \text{Normal}(-6.77, 3)\]Since these correspond to \(g/2\), we’ll divide all values by 2 when putting them into Bambi. Additionally, we know the balls landed eventually, so \(g\) must be negative. We’ll truncate the upper limit of the distribution at 0.

Now, for defining this in Bambi, the term of interest is I(Time ** 2):Planet. Often, you set one prior that applies to all groups, however, if you want to set each group individually, you can pass a list to the bmb.Prior definition. The broadcasting rules from PyMC apply here, so it could equivalently take a numpy array. You’ll notice that the priors are passed alphabetically by group name.

priors = {

"I(Time ** 2):Planet": bmb.Prior(

"TruncatedNormal",

mu=[

-9.81/2, # Earth

-3.72/2, # Mars

-6.77/2 # PlanetX

],

sigma=[

0.025/2, # Earth

0.02/2, # Mars

3/2 # PlanetX

],

upper=[0, 0, 0]

)}

planet_model_with_prior = bmb.Model(

'Height ~ I(Time**2):Planet + Time + 0',

df,

priors=priors

)

planet_model_with_prior.build()

idata = planet_model_with_prior.prior_predictive()

az.summary(idata.prior, kind="stats")

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97%

sigma 14.466 13.809 0.025 36.595

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Earth] -4.905 0.012 -4.928 -4.883

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Mars] -1.860 0.010 -1.880 -1.841

I(Time ** 2):Planet[PlanetX] -3.622 1.509 -6.360 -0.915

Time 0.520 14.788 -26.565 27.992

Here we’ve sampled the prior predictive and can see that our priors are correctly specified to the associated planets.

Next we fit the model.

planet_fit_with_prior = planet_model_with_prior.fit(

chains=4, idata_kwargs={"log_likelihood": True}, random_seed=SEED

)

planet_model_with_prior.predict(planet_fit_with_prior, kind="pps");

az.summary(planet_fit_with_prior)[0:5]

mean sd hdi_3% hdi_97% mcse_mean mcse_sd ess_bulk ess_tail r_hat

sigma 1.759 0.142 1.495 2.024 0.002 0.002 3333.0 2373.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Earth] -4.907 0.012 -4.929 -4.884 0.000 0.000 4360.0 2943.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[Mars] -1.862 0.009 -1.879 -1.847 0.000 0.000 2054.0 2614.0 1.0

I(Time ** 2):Planet[PlanetX] -2.985 0.023 -3.025 -2.940 0.000 0.000 2282.0 2772.0 1.0

Time 19.960 0.075 19.827 20.103 0.002 0.001 2025.0 2249.0 1.0

We see some improvements here! Off the cuff, these look better, you’ll notice the \(v_0\) coefficient on Time covers the true value of 20 m/s.

Now taking a look at the effects before and after adding the prior on the gravities,

earth_posterior_2 = -2 * planet_fit_with_prior.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "Earth"})

mars_posterior_2 = -2 * planet_fit_with_prior.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "Mars"})

planetx_posterior_2 = -2 * planet_fit_with_prior.posterior["I(Time ** 2):Planet"].sel(

{"I(Time ** 2):Planet_dim": "PlanetX"})

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 3, figsize=(12, 6), sharex='col')

az.plot_posterior(earth_posterior, ref_val=9.81, ax=axs[0,0])

axs[0,0].set_title("Earth $g$ - No Prior")

az.plot_posterior(mars_posterior, ref_val=3.72, ax=axs[0,1])

axs[0,1].set_title("Mars $g$ - No Prior")

az.plot_posterior(planetx_posterior, ref_val=6.0, ax=axs[0,2])

axs[0,2].set_title("PlanetX $g$ - No Prior")

az.plot_posterior(earth_posterior_2, ref_val=9.81, ax=axs[1,0])

axs[1,0].set_title("Earth $g$ - Priors Used")

az.plot_posterior(mars_posterior_2, ref_val=3.72, ax=axs[1,1])

axs[1,1].set_title("Mars $g$ - Priors Used")

az.plot_posterior(planetx_posterior_2, ref_val=6.0, ax=axs[1,2])

axs[1,2].set_title("PlanetX $g$ - Priors Used");

Adding the prior gives smaller uncertainties for Earth and Mars by design, however, we can see the estimate for PlanetX has also improved by injecting our knowledge into the model.

A deep dive into what orthogonal polynomials actually do under the hood, contributed to Bambi’s examples

Overview of polynomial regression using Bambi, through projectile motion and fictitious planets

A terminal user interface for Linear project management

A lightning-round collection of loose threads from 2025

Books I read in 2023

Who will win this year’s cup?

Books I read in 2022

Just how lucky have the 18-3 Bruins gotten?

Interoperability is the name of the game

Books I read in 2021

I got a job!

Books I read in 2020

Revisiting some old work, and handling some heteroscadasticity

Using a Bayesian GLM in order to see if a lack of fans translates to a lack of home-field advantage

An analytical solution plus some plots in R (yes, you read that right, R)

okay… I made a small mistake

Creating a practical application for the hit classifier (along with some reflections on the model development)

Diving into resampling to sort out a very imbalanced class problem

Or, ‘how I learned the word pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis’

Amping up the hit outcome model with feature engineering and hyperparameter optimization

Can we classify the outcome of a baseball hit based on the hit kinematics?

Updates on my PhD dissertation progress and defense

My bread baking adventures and favorite recipes

A summary of my experience applying to work in MLB Front Offices over the 2019-2020 offseason

Books I read in 2019

Busting out the trusty random number generator

Perhaps we’re being a bit hyperbolic

Revisiting more fake-baseball for 538

A deep-dive into Lance Lynn’s recent dominance

Fresh-off-the-press Higgs results!

How do theoretical players stack up against Joe Dimaggio?

I went to Pittsburgh to talk Higgs

If baseball isn’t random enough, let’s make it into a dice game

Random one-off visualizations from 2019

Books I read in 2018

Or: how to summarize a PhD’s worth of work in 8 minutes

Double the Higgs, double the fun!

A data-driven summary of the 2018 Reddit /r/Baseball Trade Deadline Game

A 2017 player analysis of Tommy Pham